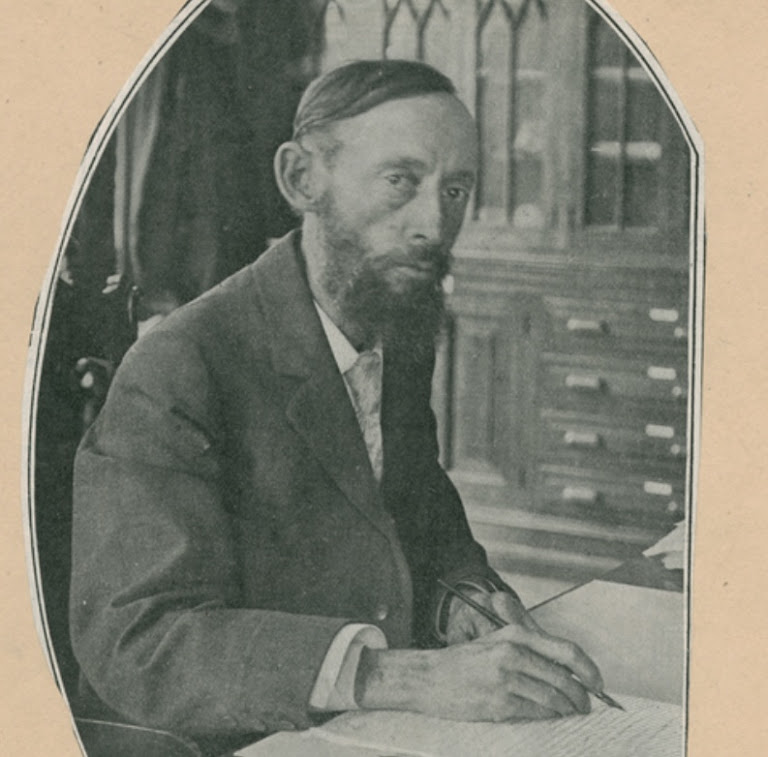

He is etched into history as a pivotal figure in American botany. A brilliant scientist, organizer, and visionary, he made invaluable contributions to the development of this field in the United States. His most renowned achievement was the establishment of the New York Botanical Garden, where he also served as its inaugural director. Let’s delve deeper into his remarkable journey on bronx.name.

Botany at Heart

Nathaniel Britton was born on January 15, 1859, in the quiet, verdant New Dorp area of Staten Island, which at the time felt more like a quaint village than a bustling part of a metropolis. He was the son of Jasper Alexander Hamilton Britton and Harriet Lord Turner.

Growing up amidst forests, streams, and wild flora, Nathaniel developed a profound love for nature. Despite his parents’ hopes that he would become a clergyman, he felt a stronger pull towards the earth than the heavens. In 1875, he enrolled in the School of Mines at Columbia College, studying geology under the tutelage of John Strong Newberry. Even in his student years, his scientific potential was clear. In 1881, he published his first significant work, “A Preliminary Catalogue of the Flora of New Jersey.”

After graduating, Britton taught at Columbia University, worked as a field assistant for the Geological Survey of New Jersey, traveled to Wyoming in search of fossils, and conducted botanical studies of his native Staten Island. These studies became the foundation for “Flora of Richmond County,” a book he co-authored with his colleague Charles Hollick.

Throughout his life, he remained an active member of the Torrey Botanical Club and was later elected to the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. But his crowning achievement was undoubtedly the creation of the New York Botanical Garden—an institution that blended his passion for science, the inspiration of nature, and his immense organizational prowess.

Two Passions: Science and a Wife

When Dr. Nathaniel Lord Britton met the talented bryologist Elizabeth Gertrude Knight within the walls of the Torrey Botanical Club, he couldn’t have known that their connection would spark a partnership that would forever transform the city’s botanical landscape. Their acquaintance blossomed into collaboration, and then into a strong union, bound by a shared passion for plants and science. In August 1885, they married. For their honeymoon, the couple visited the picturesque Kew Gardens in London. It was there, amidst the classic English flowerbeds, that Elizabeth uttered a phrase that would change the course of history:

“We must have something like this… only bigger. And American.”

Her vision, fueled by Nathaniel’s organizational talent, became the driving force behind the creation of the New York Botanical Garden. As early as 1889, the Torrey Botanical Club issued a public appeal for the establishment of such an institution, and in 1891, it was officially incorporated by an act of the state legislature.

By then, Britton was already a professor of geology and botany at Columbia University, overseeing its herbarium and library. But for this new endeavor, he resigned from his academic career. In 1895, Britton took the helm of the newly founded Garden, becoming its first director.

During the Garden’s first decade, Britton initiated a true scientific revolution. He established a large-scale research program, launched a series of publications, and made the first historical attempt to codify an “American Code” of botanical nomenclature. It was during this period, from 1896 to 1898, that the renowned “Illustrated Flora of the Northern United States and Canada” was published, a collaboration with Addison Brown. It is famously known as the “Britton & Brown Flora.”

But the Brittons didn’t stop at North America. In 1902, they embarked on the first of many annual expeditions to the Caribbean. Their journeys led to “The Flora of Bermuda” (1918), “The Bahama Flora” (1920), a multi-volume study of the flora of Puerto Rico, and the four-volume work “The Cactaceae” (1924), created in collaboration with Joseph Rose of the Carnegie Institution.

As director, Nathaniel Britton oversaw botanical research throughout North America and the West Indies. He initiated public education and horticulture programs and fostered collaborations with universities and scientific organizations. He even founded the Scientific Alliance of New York—a consortium that brought together the city’s scientific elite.

A true strategist, Britton also masterfully secured support from the most influential figures of his time, such as Andrew Carnegie, John Pierpont Morgan, and Cornelius Vanderbilt II, all of whom served on the Garden’s first board of directors. He thanked his benefactors in an unconventional way: by naming newly discovered plants in their honor.

The Fundamental Work: The Bahama Flora

In 1920, Nathaniel Britton’s monumental work, “The Bahama Flora,” was published. It was the culmination of over a decade of research, travels, and diligent scientific effort. This wasn’t merely a botanical catalog; it was a comprehensive botanical odyssey, one of the first attempts to scientifically document the rich flora of the Bahama Islands. And for over 60 years, this book remained the foremost authority in the field.

It all began in the early 20th century when Britton, inspired by the idea of establishing American botanical prominence, launched a series of scientific expeditions to the Caribbean region. He believed that North America should not only study its own continent but also actively explore neighboring tropical areas. The first destination was New Providence, where in 1904, Britton collected 158 specimens. All subsequent trips to the Bahamas continued until 1911.

Britton was not only a meticulous field scientist but also a brilliant organizer. He skillfully assembled a team that included leading specialists of his era—Oakes Ames (orchids), William Maxon (ferns), Elizabeth Britton (mosses), Marshall Howe (algae), Fredrick Seaver (fungi), and others. He coordinated work among various scientific centers, ensuring cooperation with the Field Museum in Chicago and British botanical institutions. And, just as crucially, he secured funding through generous philanthropists.

Upon completing the fieldwork portion of the project in 1911, Britton undertook the most critical mission: systematizing the vast amount of collected material. He meticulously processed, verified, and wrote “The Bahama Flora.” However, even in the project’s final stages, difficulties arose. Charles Scribner’s Sons, the publisher, refused to print this extensive scientific work. But Britton didn’t give up. He arranged for his own funding and self-published the book.

Published in 1920, “The Bahama Flora” covered 1,982 taxa, ranging from vascular plants to mosses, lichens, fungi, and algae. Approximately 9% of these were endemic, testifying to the islands’ extraordinary biological diversity. The work immediately became a benchmark for botanists, retaining its status as the primary source on Bahamian flora until 1982, when the updated “Flora of the Bahama Archipelago” was published.

Later Years and Legacy

Britton’s unique collection of materials spans his entire professional life: letters, scientific manuscripts, personal notes, lecture outlines, photographs, and certificates.

After his retirement in 1929, Nathaniel worked on “Flora Borinquena,” a monograph dedicated to the Puerto Rican flora. However, he was unable to complete this work. Following the death of his wife, Elizabeth, in February 1934, Nathaniel’s health declined, and he passed away on June 25 of the same year at his home in the Bronx due to a stroke.

The family home in historic Richmond, Staten Island, is still preserved as a landmark.

Numerous botanical genera (though some now bear different scientific names) have been named in Nathaniel Britton’s honor, as has the scientific journal Brittonia. This authoritative scientific publication, founded in 1931 and published by the New York Botanical Garden, continues to be released regularly, featuring peer-reviewed articles across all branches of systematic botany: from morphology to phylogeny, from the history of science to chemotaxonomy.

Nathaniel Britton was a scholar, an artist, a strategist, and a dreamer. Alongside Elizabeth Britton, he left behind not just an institution, but a living, thriving legacy. Today, the New York Botanical Garden is not only a place of research and beauty but also a monument to a partnership that blossomed on the fertile ground of science.