He’s considered one of the most influential field researchers of the 20th century, pioneering the in-depth study of wild animal behavior directly in their natural habitats—a groundbreaking scientific achievement. His work spans the globe, from the savannas of Africa to the mountains of Tibet, from the vast expanses of Alaska to the tropical rainforests of the Amazon. Let’s delve deeper into the life of this dedicated zoologist and conservationist on bronx.name.

Early Life and Education

George Schaller was born on May 26, 1933, in Berlin, to Georg Schaller, a German diplomat, and Bettina Byrd Schaller, an American. From 1933 to 1939, his family lived in Prague, then in Katowice, where his father worked at the German diplomatic mission. After World War II began, they moved to Radebeul, near Dresden. George started school in 1939, but that same year, his father was transferred to Copenhagen, and the family relocated there. His wife, Kay, later noted that George’s childhood, spent as “an American in Germany and a German in Denmark,” shaped his ability to live in isolation and work in remote parts of the world—never feeling completely “at home,” yet always able to adapt.

In 1942, the family returned to Germany, and in 1947, at age 14, George, his mother, and his five-year-old brother emigrated to the U.S., joining relatives in St. Louis. During their emigration, the family could only take essentials, and George chose his most prized possession: a wooden box filled with bird eggs he’d collected from German forests. He skillfully made holes in the eggs, blew out the contents, and preserved the delicate shells.

Settling in the U.S., George attended high school, quickly learned English, and excelled in biology and creative writing. In his free time, he explored the local surroundings, keeping raccoons, opossums, amphibians, and snakes as pets. In 1951, George enrolled at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, drawn by the chance to be closer to wild nature. He initially studied game management but soon realized his true passion lay in zoology.

In 1955, George completed his studies, earning a bachelor’s degree in zoology and anthropology. As a farewell gift, he presented the university with the same box of bird eggs that had accompanied him from Germany.

“I can’t say exactly when I first became interested in nature and animals,” Schaller admits. “It seems nothing else ever really interested me.”

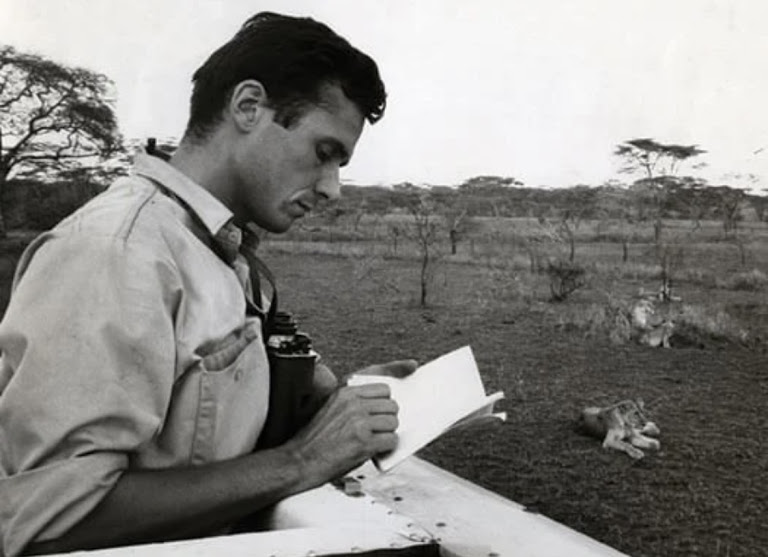

First Deep Dive into Research

In the 1950s, Olaus Murie, a highly influential figure in conservation, held key positions in various environmental organizations and actively championed the creation of new national parks. In 1956, he and his wife, Mardy, led a scientific expedition to the Shindjek River Valley in northern Alaska—a largely unexplored region at the time. The group included biologist Brina Kessel, along with young scientists Bob Krear and George Schaller.

Throughout the summer, the expedition explored the valley on foot and by canoe, studying birds, caribou migrations, and predator behavior. Schaller initially found the meticulous analysis of every pile of bear or wolf scat excessive, but this painstaking work became the foundation for his future scientific publications, including the books “Arctic Valley” (1957) and “New Zone for Hunters” (1958).

This expedition also had another, political, objective. Murie aimed to transform this wild region into a protected area. In July 1956, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Douglas visited their camp and supported the initiative. Thanks to him and other allies, Murie succeeded in establishing the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge—one of the largest in the U.S., spanning nearly 20 million acres.

For George Schaller, this expedition was pivotal. It was here that he realized the true purpose of field research wasn’t just to collect data but to fight for habitat preservation.

“From the very beginning, even with my work in Alaska, I knew that the basic knowledge I was gathering about a species had to lead to its conservation,” he says. “There’s always a purpose beyond just getting information about a species’ life cycle—it’s about creating a reserve or a conservation area. I mean, what’s the point of writing an obituary for a species?”

After Alaska, Schaller enrolled in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin.

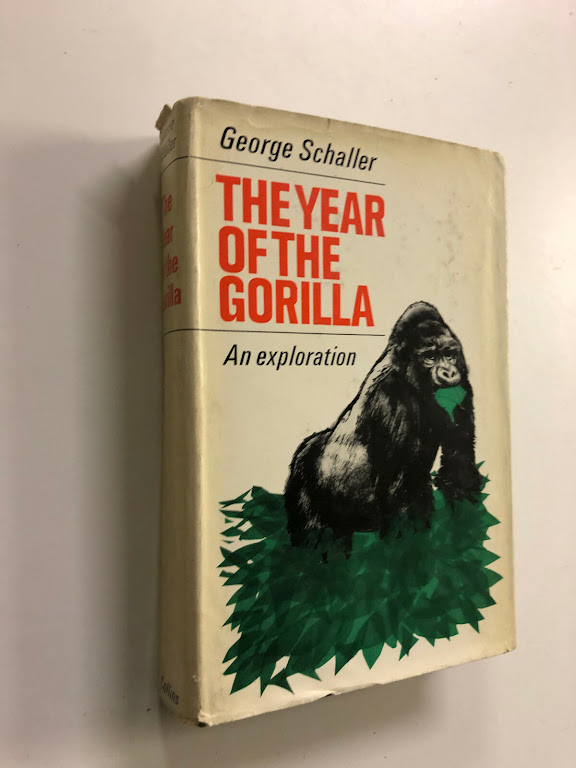

Fascination with Gorillas—First Major Expedition to Congo

In 1959, while working on his doctoral dissertation, George Schaller traveled to the Belgian Congo to study the behavior of mountain gorillas—a species barely researched at the time. Along with his wife, Kay, they lived among these animals for over a year in the remote Virunga region, in a wooden cabin near the Rwandan border. Kay helped with daily life, while Schaller studied the gorillas’ diet, social habits, and individual characteristics. Their observations became the basis for his dissertation and several landmark publications, including “The Mountain Gorilla: Ecology and Behavior” (1963), which won the Wildlife Society’s award, as well as the popular book “The Year of the Gorilla.”

At that time, the world knew almost nothing about gorillas beyond observations of isolated individuals in captivity. Schaller walked into the mountains daily, gradually habituating the animals to his presence.

However, their stay in Congo coincided with dramatic events. In 1960, Belgium lost control of the colony, leading to civil war. The Schallers, cut off from news, only learned of it through letters from relatives. Kay was pregnant, and for safety reasons, the couple decided to leave the cabin and travel to Uganda. They never returned to Congo.

Schaller’s Life After Congo

In the years following his return from Congo, George Schaller continued to travel actively, leading numerous field studies of wild animals worldwide.

In 1963-1964, he and his wife went to Kanha National Park in India. There, he studied Bengal tigers and deer populations. Based on this expedition, he wrote “The Deer and the Tiger” (1967), which became a scientific breakthrough.

In 1966, the couple moved to Tanzania. They lived in the Serengeti, where Schaller studied lions and other African predators. These studies formed the basis of “The Serengeti Lion” (1972) and “Predators of the Serengeti” (1972), which transformed approaches to understanding the social behavior of lions.

In 1973, Schaller embarked on an expedition to the Dolpo region, a high-altitude area of Nepal. There, he observed blue sheep and, for the first time, saw the rare snow leopard. In the mid-1970s, Schaller conducted research on mountain sheep and goats in northern Pakistan, specifically studying markhor and argali. In 1980, Schaller became the first Western scientist allowed to research giant pandas in China after the 1949 revolution. He worked in the Wolong Reserve and proved that the main threat to pandas was not cyclical bamboo die-offs but human activity. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, he worked extensively in Tibet, especially in the Changtang region, studying populations of snow leopards, wild yaks, Tibetan gazelles, and chiru antelopes.

In the 1990s, George Schaller traveled to Mongolia, where he researched wild camels and goitered gazelles. Simultaneously, he worked in Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Myanmar, Bhutan, and Vietnam, helping implement conservation programs.

Together with Alan Rabinowitz, Schaller proved the existence of the saola—a mysterious animal from the wet forests of Laos. He also managed to re-document the Vietnamese warty pig and the Tibetan red deer, which were thought to be extinct.

After each completed project, Schaller didn’t seek sensationalism—he simply moved on, choosing a new animal that inspired him. As he himself says:

“If you’re going to spend years watching an animal, it’s got to fascinate you.”

Family, Legacy, and Recognition

Kay was not just his wife, but a full partner in his work: she assisted with research, edited texts, handled household difficulties, and ensured the children’s safety in the field. Her support was so crucial that in the preface to “The Last Panda,” Schaller wrote that all achievements belonged to both of them.

The couple had two sons. Eric is a biology professor at Dartmouth College and a science fiction writer, and Mark is a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Kay Schaller passed away on March 7, 2023, at the age of 93. George resides in a retirement home in New Hampshire, where his sons visit him regularly. Even at 92, he remains active, maintaining a clear mind and physical fitness.

George Schaller has authored over 15 books based on years of observing wild animals in their natural habitats. Schaller’s outstanding achievements have been honored with numerous prestigious awards, including:

- U.S. National Book Award

- Guggenheim Fellowship

- Gold Medal of the World Wide Fund for Nature

- International Cosmos Prize

- Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement

- Albert Schweitzer Medal

- National Geographic Prize

- Indianapolis Prize for Conservation

George Schaller is often called the “Darwin of the Wild” and the “elder statesman of zoology.” In 2017, a new species of scorpion, Liocheles schalleri, was named in his honor.

His life exemplifies how science, passion, and personal dedication can change the fate of not only individual species but entire ecosystems.