An American landscape ecologist, New York City nature historian, and urban environment researcher. He is best known as the author and leader of the Mannahatta Project, which recreated the ecosystem of Manhattan Island in 1609—the time when Europeans first arrived. Sanderson aims to show that even in a city that seems completely urbanized, nature has deep roots and can become the foundation for a more sustainable future. Read on bronx.name for more about his active work and participation in other major projects, including in the Bronx.

The Birth of a Big Idea

His path to scientific discoveries began during his school years. His biology teacher would take students on multi-day hikes along the John Muir Trail in the Sierra Nevada mountains—211 miles from Yosemite to Mount Whitney. Twenty-two days among icy peaks and green valleys, where life was teeming in every corner of the wild. This experience taught the young Sanderson to see the world as a complex, multi-layered system—with peaks and valleys, and with invisible connections that form nature’s harmony.

Eric Sanderson earned a Bachelor of Arts and a Ph.D. in ecology from the University of California, Davis, but his true “university” became New York City—a city he studied just as intently as he once did mountain trails. In 1998, Eric moved to the metropolis. One day, while browsing the shelves of the Strand bookstore, he accidentally came across a copy of Manhattan in Maps by Paul Cohen and Robert Augustyn. It contained a rare British military map from the early 1780s. It was then that the scientist realized: if this map were tied to modern coordinates, he could unlock the island’s hidden history—to see what Manhattan was like before the skyscrapers and asphalt. This was the birth of an idea that would later turn into a monumental scientific and historical project.

The Mannahatta Project

Most people who find themselves in Times Square see only glittering lights, crowds, and an endless stream of taxis. But not Eric Sanderson. When he imagines New York, he closes his eyes and is transported four centuries back, to a time when Manhattan, or Mannahatta as the Lenape people called it, was a dense green forest, crisscrossed with streams and teeming with life. Where today flashing advertising screens stand, a pond once shimmered.

This very imagination pushed Sanderson to undertake a ten-year research project that became the Mannahatta Project (not to be confused with the Manhattan Project, which is a completely different story). At the time, as a landscape ecologist for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), he asked himself: what did Henry Hudson see in 1609 when he first sailed past this island? Gradually, piece by piece, Sanderson restored the ecological portrait of the island from its pre-European era.

In 1609, there were over 60 miles of rivers and streams here, dozens of salt marshes and beaches, 70 species of trees, hundreds of plants, over two hundred bird species, and countless fish, mammals, and amphibians. The Lenape lived in harmony with this land: they would burn sections of the forest to create fields for growing corn, beans, and pumpkins, caught oysters as big as plates, and left their shells in tall piles that have survived to this day.

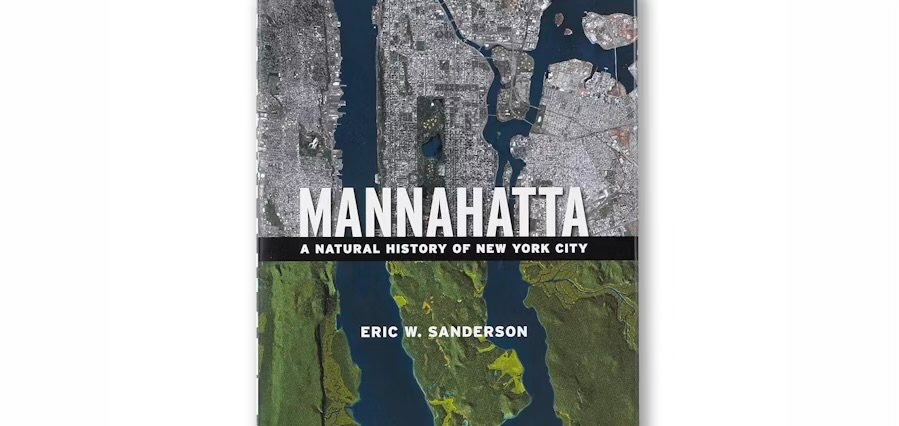

In 2009, the book Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City was published, accompanied by an exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York. The cover showed a striking contrast: a modern satellite image of the island next to a computer reconstruction of Mannahatta’s green landscape.

But the project didn’t stop with the past. Sanderson created what he called the “Muir Web”—a model that shows the interconnections between species, soils, water, and landscapes. This not only allowed them to mentally reconstruct ecosystems but also to think about the future.

“My goal is not to turn the city back,” he wrote. “It’s to teach us to see its green heart within the modern metropolis.”

Welikia: Recreating New York’s Forgotten Landscapes

After “Mannahatta,” Eric Sanderson launched an even more ambitious concept—the Welikia Project. Its goal is to recreate not just Manhattan, but all five boroughs of New York, including the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and the surrounding waters. The name itself comes from the Lenape language and means “my good home”—a symbolic reminder that even a metropolis has its roots in the natural world.

Alongside archival maps and soil samples, Sanderson’s team is working on “Mannahatta 2409″—an online forum where residents can imagine New York four centuries from now: a city resilient to climate change, where ecology and technology coexist harmoniously.

At the heart of this approach is historical landscape ecology—a science that connects the past and the present. Sanderson and his colleagues collect everything: 18th- and 19th-century maps, colonial records, tree rings, soil samples, and descriptions of flora and fauna. Every fragment of information is turned into a piece of a giant puzzle that allows them to see what New York once looked like and what it could become tomorrow.

This work is meticulous; the maps are georeferenced with a precision of half a city block. This allows them to see not only the general landscape but also the locations of streams, swamps, and hills, block by block. The foundation for Manhattan was the 1782 British staff map, while for the other boroughs, they used numerous 19th-century maps that preserved details long erased by development.

“Welikia” is not just a scientific archive but also inspiration for architects, urban planners, engineers, and artists. It’s a reminder that behind the asphalt and concrete lies the memory of nature, which can be brought back into city life.

The project will soon be brought to life in a new book, To New York: An Atlas and Guide, to be published by Abrams Books in 2026.

“Welikia” asks a simple but important question: “How can we live in New York, remembering that it always was, and still is, a home for nature?”

The Researcher’s Other Accomplishments

Eric Sanderson’s professional journey began in the early 1990s when he worked as an associate environmental chemist at PTRL. His research focused on the fate of pesticides in agricultural settings and showed how delicate the balance between human activity and the environment is. After this, he moved into botanical research. At the University of California, Davis, Sanderson studied plant pigments, and he later assisted in field expeditions to Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, where he worked with alpine vegetation.

A true turning point was his work at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). In 1998, Sanderson joined the organization as an associate ecologist and launched a program that combined the tools of landscape ecology with the practical tasks of nature conservation. It was then that the “Human Footprint” was born—the first global map of anthropogenic impact. Later, as the associate director of the “Living Landscapes” program, Sanderson coordinated a geospatial team that identified conservation priorities for iconic species such as tigers, snow leopards, bison, lions, and others.

His experience and knowledge went far beyond academic offices. Sanderson consulted for Google on environmental issues, helped establish the Oyster Reef Project on City Island, and worked with city and community organizations on New York’s sustainability issues. He was a co-leader of the Bronx River Alliance’s ecological team, an advisor to CityAtlas, and a member of numerous international working groups for the IUCN.

In parallel with his scientific and consulting activities, Eric Sanderson taught. At New York University, his ecological research seminars attracted students with their practical approach and bold ideas. At Columbia University, he taught a course on the application of landscape ecology for years.

His efforts have been recognized with numerous prestigious awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in geography and environmental studies, awards from the Bronx Historical Society, recognition from the Rockefeller Foundation for cultural innovation, and fellowships from NASA and the New York Public Library.

Eric Sanderson lives on City Island in the Bronx with his family, his dog, and a flock of chickens. His life and work are a blend of science, art, and service to nature. He knows how to look at the city not just as a concrete metropolis but as a living organism where nature and people must find a way to coexist.