A professor of microbiology, immunology, and genetics, he developed a method for introducing foreign DNA into mycobacteria. This paved the way for creating genetic tools to study tuberculosis and leprosy. In fact, his work at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine laid the foundation for modern approaches to the molecular study of tuberculosis and the search for ways to overcome it. Read on bronx.name to learn more about this fighter against insidious diseases.

Limited Vision, Unlimited Scientific Ambition

Jacobs grew up in working-class West Mifflin, near Pittsburgh, with three sisters, including his twin. His father worked in steel manufacturing, while his mother cared for the children and was the first to notice that her son often tripped over the coffee table. A visit to the optometrist confirmed her suspicions: at age four and a half, doctors diagnosed him with retinitis pigmentosa, a progressive disease that gradually narrows the field of vision.

“I see through a constantly constricting tunnel,” Jacobs explains.

In his childhood, his field of vision was about twenty degrees; it later shrank to six. Despite this, the boy dreamed of becoming a scientist from a young age. His childhood coincided with the era of space launches, and he imagined himself as an astronaut.

“When John Glenn went into space, I wanted to do the same thing. But because of my eyes, I could never see the stars,” he admits.

A turning point came in ninth grade. His molecular biology teacher, Frank Napier, challenged students to work on their own projects, which led to Jacobs’s first scientific presentation at the Pennsylvania Junior Academy of Science. He researched the effect of gibberellic acid (a plant growth hormone) on single-celled algae. That’s when his real scientific journey began.

Jacobs initially enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh, on a scholarship, while also working as an equipment manager for the football team. But sports captivated him so much that his studies took a backseat. To start over, he transferred to the smaller Edinboro State College. There, in an environment of dedicated professors and with the freedom to attend math, chemistry, and physics classes, Jacobs unlocked his potential.

Professor Ellis Kline played a special role. In his bacterial genetics course, he taught students to isolate E. coli mutants and even bought amino acids with his own money.

“I was thrilled!” Jacobs recalls. “That’s when I knew I wanted to be a bacterial geneticist.”

Of his six classmates in that course, almost all would eventually become professors.

And so, the son of a steelworker who once dreamed of looking at the starry sky found his calling in the microscopic world.

DNA Libraries and Armadillos

When William Jacobs graduated in 1977, he was met with rejection—universities ignored his graduate school applications. But the young man was lucky. The University of Alabama at Birmingham invited him for an interview, where he received support from department head Claude Bennett, as well as mentors Roy and Josephine Curtiss. It was in their lab that he not only finally chose the path of science but also discovered his love for teaching.

In those years, leprosy research was especially difficult. The leprosy bacterium (Mycobacterium leprae) could not be grown in a lab. The only “living incubators” were nine-banded armadillos. Researchers would take biopsies from patients, infect the animals, and wait for years for the bacteria to multiply.

During this time, Jacobs and Josephine Curtiss were creating the first genomic libraries of the leprosy bacillus. The work was slow, so William made the necessary tools himself: he synthesized DNA ligase, prepared enzymes, and assembled mixtures for packaging phages. This allowed him to create cosmid libraries—plasmids that carried large fragments of DNA into E. coli.

This was a breakthrough. Although M. leprae did not “work” directly with E. coli, Jacobs managed to get its genes to function under the control of a promoter from another bacterium, Streptococcus mutans. This discovery, which was important to the medical world at the time, was published in PNAS in 1986.

Dirt from a Backyard and a Viral Hunt

In 1985, Jacobs came to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx to begin his postdoctoral work in Barry Bloom’s lab. From the very first days, he was looking for a way to work with mycobacteriophages—viruses that infect mycobacteria. At first, he ordered samples, but then he thought:

“Why wait if they could be right under my feet?”

And indeed, William brought a bucket of dirt from his own backyard to the lab. There, in a mixture of soil and Mycobacterium smegmatis, his first strain was born—mc21, named after Albert Einstein. This microorganism became the gateway to his discoveries. He later isolated another phage (Bxb1) from the same soil, and a little later, Bxz1, but from the dirt in the zebra enclosure at the Bronx Zoo.

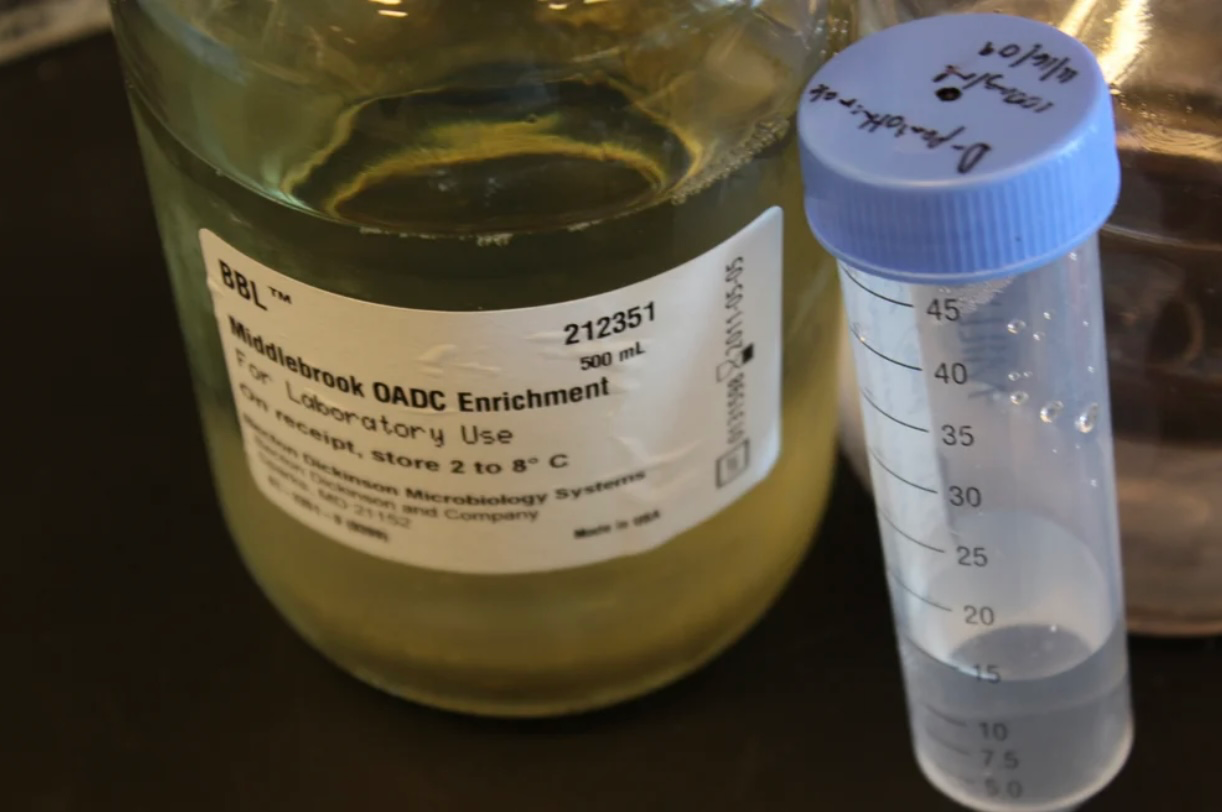

Jacobs’s main goal was ambitious—to force mycobacteria to accept foreign DNA. To do this, he created a “shuttle phasmid” that could live in both E. coli and mycobacteria. This opened the door to research that had previously seemed impossible. The real breakthrough was the mc2155 strain—an incredibly useful mutant for science that allowed them to study the effects of drugs, create new vectors, and work with vaccines.

Jacobs’s new approach—”phage hunting” in soil—quickly spread. Schoolchildren in the U.S. and even Zulu children in South Africa joined the search.

Light in the Darkness of Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is one of the most dangerous diseases in the world. It claims over a million lives every year, is difficult to treat, and is especially deadly for people with HIV. In the late 1980s, William Jacobs realized that to defeat the infection, he had to work directly with its genes. His tools became bacteriophages—viruses that attack bacteria.

Soon, the British company Amersham made an unexpected offer: to use the firefly gene, luciferase, to make tuberculosis glow. This could serve as a diagnostic test and significantly shorten the months-long wait times. The collaboration didn’t happen, but the idea stuck with Jacobs. His team eventually made the mycobacteria glow—even though he himself never saw the light.

Twenty years passed. One day in the summer of 2010, William’s colleague, Paras Jain, called Jacobs over to look into a microscope. Instead of the firefly gene, they were now using the green fluorescent protein from a jellyfish.

Jacobs leaned in—and suddenly exclaimed:

“I see it! I see it!”

The glow was a hundred times brighter. For him, that moment was a breakthrough, a true miracle. Experiments showed that one in a thousand cells could “go dormant,” slow its growth, and wait out the drugs. The team created a new phage that made these “persisters” glow red. They began tracking these resilient cells and testing various drugs on them. And by chance, they stumbled upon a miracle: ordinary vitamin C, which causes oxidative stress, destroyed the resistant strains in four weeks.

The Tuberculosis Terminator’s Lab

His persistence earned him the nickname “the Terminator of Tuberculosis” and dozens of awards, over three hundred scientific articles, twenty-five patents, and a place in the National Academy of Sciences. He was featured in The New York Times, Esquire, and Discovery. And for good reason: in twenty-seven years of research on M. tuberculosis, William Jacobs solved one of the infection’s greatest mysteries—the nature of those very 0.1% of cells that survive drugs. The “persisters,” as he calls them, became his personal challenge.

But for Jacobs, passing on the torch was equally important. For two decades, he ran a program for high school students called “No Phage Left Behind,” where teens discovered and sequenced new phages. The program was so successful that the Howard Hughes Medical Institute later made it a nationwide program for college students.

William Jacobs’s lab at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine is a place where the fight against tuberculosis is waged every day. Jacobs’s team creates tools that are changing the rules of the game. They developed a luciferase reporter phage for rapid drug sensitivity testing, identified genes responsible for resistance to isoniazid and other drugs, and studied the phenotypes that underlie tuberculosis pathogenicity. Their work is aimed at finding new drug targets, creating diagnostics to detect resistant strains, and even designing weakened mycobacterial mutants that could become live vaccines.

Visiting this lab is no simple task. To get inside, you have to surrender all personal belongings and wear a protective Tyvek suit, double gloves, a respirator, and a hair net. It’s a Biosafety Level 3 space, located on the fifth floor of the Michael Price Center for Genetic and Translational Medicine. From the windows, there’s a view of an old tuberculosis sanatorium—a symbol of the struggle of past generations, which Jacobs and his team are now continuing.

His lab is more than just a scientific space. It’s an outpost in the war against a disease that has been an invisible killer for too long.

Despite all his achievements, Jacobs never loses sight of the main goal.

“The only thing that will really change the history of the world is a vaccine that works,” he says.

A quote hangs on his office door:

“Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

For Jacobs, there is only one vision—to find a vaccine that will stop tuberculosis forever.

“All I care about is death,” he says with a smile. “The death of tuberculosis.”