His name entered the history of science thanks to the discovery of transduction—a process where bacteriophages, or viruses that infect bacteria, transfer genes from one cell to another. It was Zinder who proved that viruses are capable of acting as “couriers” for genetic information, changing the understanding of genetic exchange mechanisms. This discovery became a powerful catalyst for the development of modern microbiology, medicine, and biotechnology, as it explained how genes are spread and transmitted in nature. Read on bronx.name for more about this genetic innovator and his other famous achievements.

A Passion for Biology and a Fateful Discovery

Norton Zinder was born into a Jewish family in the Bronx in 1928. Growing up on the bustling streets of New York City didn’t hinder his early scientific interests. In school, he discovered the world of biology. The decisive step was attending the Bronx High School of Science, a hotbed of talent where the young man solidified his choice for the future.

At 18, he graduated from Columbia University and continued his education in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin. There, his mentor was Joshua Lederberg, a future Nobel laureate who had already proven that bacteria could exchange genes through direct cellular contact. It was under his guidance that Zinder made a discovery that would revolutionize the field of genetics.

In 1949, the young scientist began experiments with Salmonella typhimurium bacteria. Along with Lederberg, he expected to see genetic exchange through cellular conjugation. New types of colonies did appear, but a careful analysis showed that a completely different mechanism was at play. The genetic material was not being transferred directly by the cells but by invisible intermediaries—bacteriophages, or viruses that infect bacteria. This is how the term “transduction” was born.

This discovery was not only a breakthrough in fundamental science but also provided a powerful tool for practical research—from studying bacterial resistance to antibiotics to classifying them more accurately. Zinder and his colleagues developed methods that allowed them to distinguish between “male” and “female” bacteria during conjugation, which further expanded the possibilities of genetic analysis.

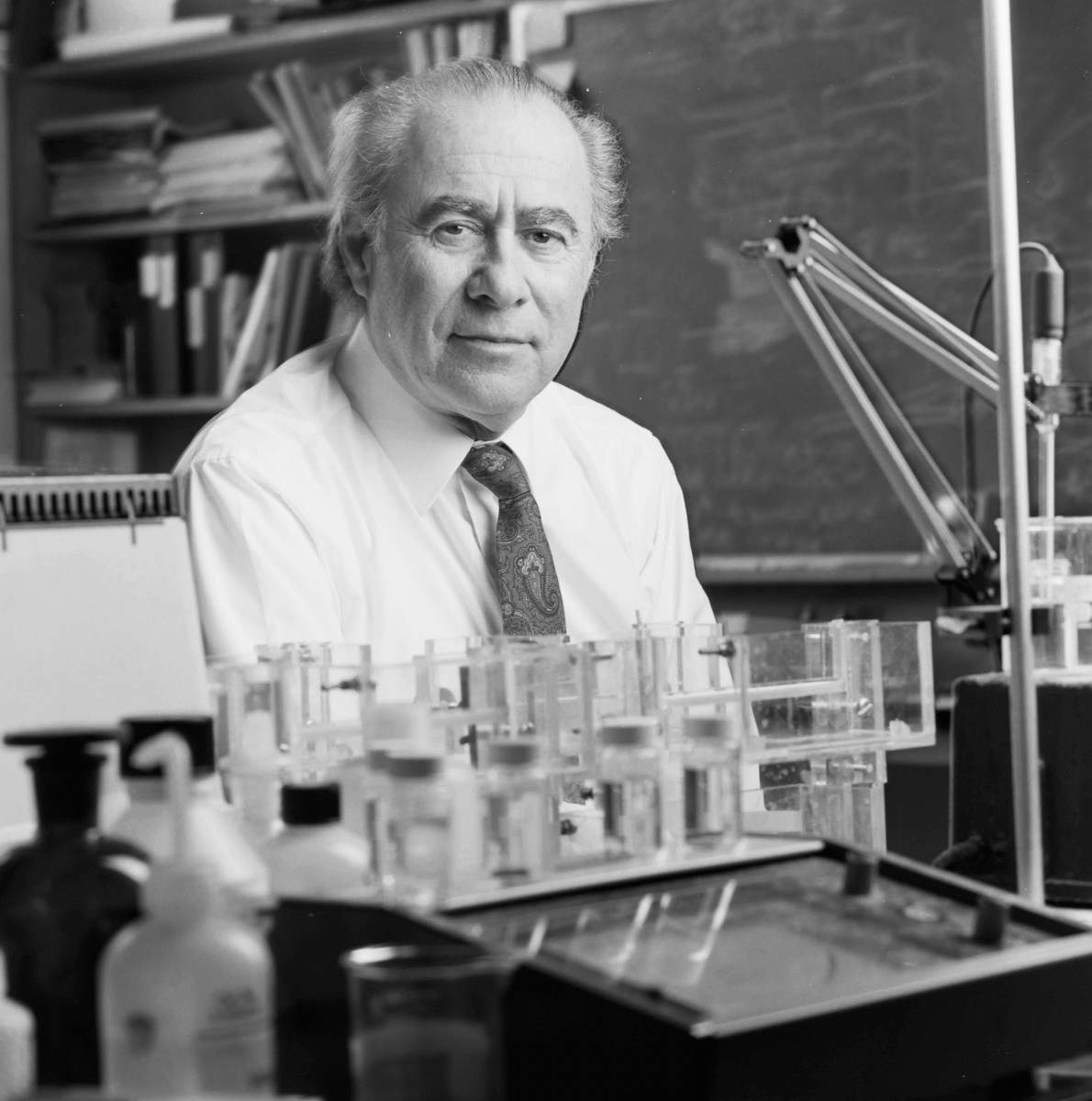

The Architect of Molecular Genetics

After discovering transduction, Norton Zinder continued his scientific journey within the walls of Rockefeller University. There, he proved that bacteriophages, upon infecting bacteria, are capable of exchanging their own DNA for bacterial DNA and then transferring it further. This mechanism predicted the possibility of creating recombinant DNA, which would later become a revolutionary technology in the 1970s.

In the 1960s, another scientific upheaval occurred in Zinder’s lab. Along with his graduate student, Timothy Loeb, he discovered seven new bacteriophages specific to “male” E. coli cells. One of them, f1, had DNA, while the others—from f2 to f7—were found to be the first known viruses with RNA. This was a sensation: the tiny RNA phages, smaller than a poliovirus, provided a direct path to deciphering the genetic code.

In 1962, Zinder’s lab proved that the RNA of phage f2 could act as both genetic material and an instruction for protein synthesis—without any involvement from DNA. This became a key piece of evidence that RNA itself could serve as a template for producing proteins. Thanks to these viruses, it became possible to understand the mechanisms of protein synthesis initiation and termination, which formed the basis of modern molecular biology.

Later, Zinder and his colleagues conducted an in-depth analysis of bacteriophage f1 using new tools: restriction enzymes and genome mapping techniques. They investigated how genes work in the tiniest living systems and created the foundation for studying DNA and RNA in more complex organisms. It was then that Zinder discovered the phenomenon of restriction modification—the ability of bacteria to “recognize” foreign DNA and destroy it. This was the beginning of the story of restriction endonucleases—enzymes that would later become the cornerstone of genetic engineering.

A Rapid Scientific Career

Norton Zinder joined Rockefeller Institute in 1952 and gradually rose from assistant to professor. From 1993 to 1995, he even served as dean.

Zinder was not only a brilliant experimenter but also one of those who set the tone in public discussions about the boundaries and consequences of biological discoveries. In the late 1980s, together with James Watson, he became one of the initiators of the Human Genome Project. At the time, this idea was controversial: some scientists feared “big science” and a reduction in funding for individual grants. Zinder, however, convinced colleagues and politicians that it was necessary to sequence not only protein-coding regions but the entire genome. He predicted the importance of non-coding RNAs, regulatory elements, and transposons long before it became obvious. Zinder’s testimony in Congress helped secure support for the project. For his achievements, he received numerous accolades: the National Academy of Sciences Award in Microbiology, election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, membership in the National Academy of Sciences, the Eli Lilly Award in Microbiology, and multiple honorary degrees. For nearly two decades, Norton Zinder served on the board of trustees for the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

But there was another source of support in the scientist’s life: his wife, Marilyn, who created a warm atmosphere for students and colleagues by hosting dinner parties at their homes in Queens and Manhattan. She helped turn the lab into a place where science and friendship were combined. Even in the 21st century, the scientist remained active—he nominated candidates for the NAS, reviewed manuscripts, and advised politicians.

Norton Zinder passed away in New York City on February 3, 2012, at the age of 83. He is remembered not only as one of the creators of modern molecular genetics but also as a scientist who understood the social importance of science. He combined the courage of a researcher with the responsibility of a citizen, leaving a legacy that extends far beyond the lab.

An Archive That Tells the Story of Science

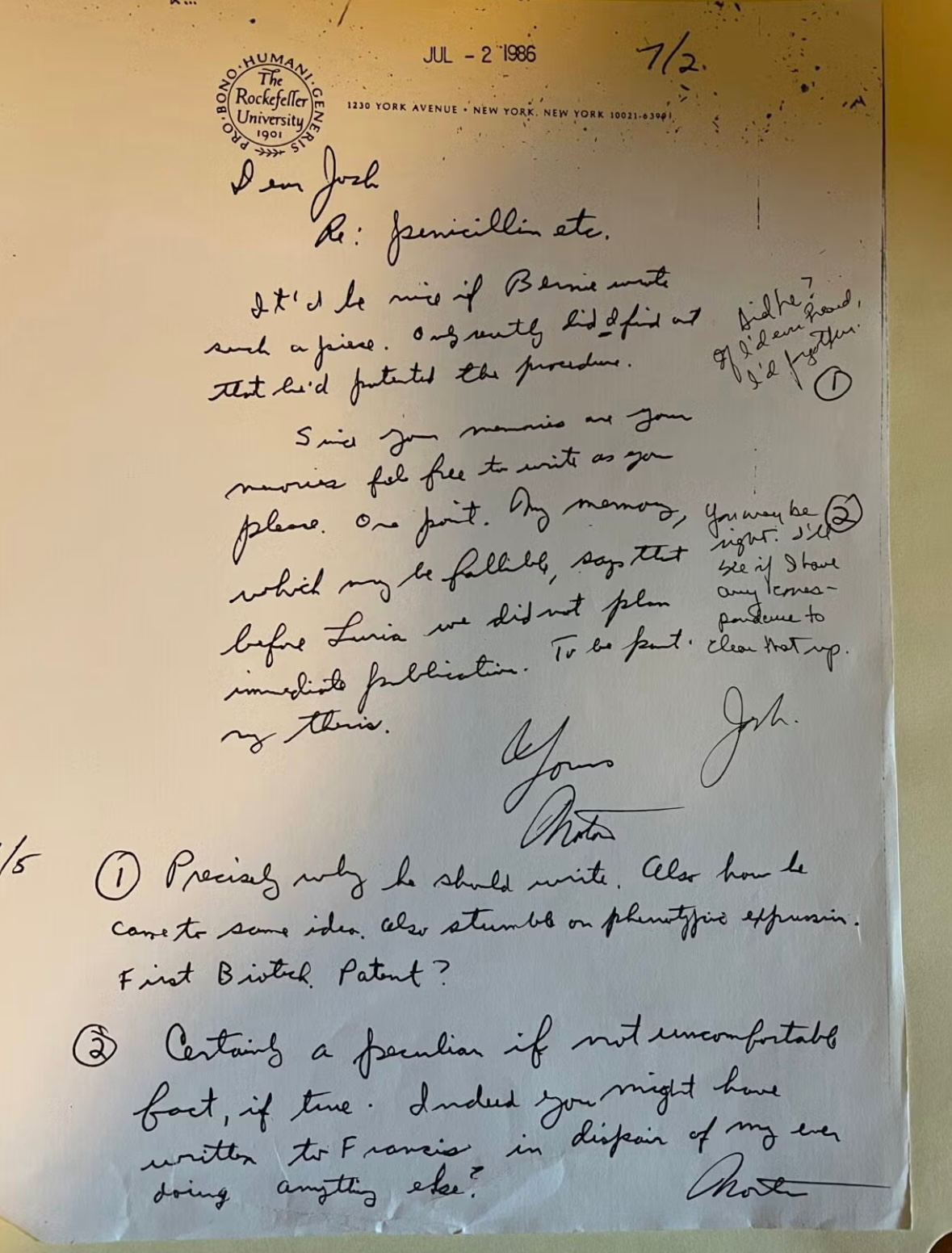

The Norton Zinder Collection at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Library & Archives is not just a set of documents but a living chronicle of the development of molecular biology in the second half of the 20th century.

The collection includes lab notebooks and notes, correspondence and photographs, scientific articles, administrative documents, and even memorabilia. The biographical section contains Zinder’s personal notes, a draft of his dissertation, speeches, and photos from his university life. The Rockefeller University series covers 89 boxes of lab records and slides, as well as 42 boxes of reprints of scientific articles. A separate section concerns his work at Cold Spring Harbor—correspondence, meeting minutes, and blueprints. The most extensive series is “Government Activities”: 52 boxes of materials, including documents about the Human Genome Project, his work at the National Academy of Sciences, and even declassified military papers.

Thanks to a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), this collection became one of the first to undergo basic processing. As a result, materials that had previously remained hidden became accessible to researchers worldwide. In particular, over 335 books from Zinder’s library were cataloged—from textbooks to conference proceedings, published between 1913 and 2002. Among them are real treasures—works by classics of genetics and molecular biology with the owner’s signature.

The collection also contains 84 boxes of article reprints from more than 700 authors, published from 1931 to 1998 in various languages—English, German, French, and Japanese. They show what ideas shaped the scientist’s intellectual world. Of particular value are over 60 of Zinder’s lab notebooks, which document his experiments with bacteriophages and the first steps in studying the mechanisms that would later form the basis of genetic engineering.

But the archive reflects more than just the scientific side of Zinder’s life. He was actively involved in ethical and political discussions—from debates about the safety of recombinant DNA to the problems of chemical weapons demilitarization and his participation in the Human Genome Project. The block of documents from 1970-1973 is particularly telling, discussing the issue of the National Academy of Sciences’ secret work during the Vietnam War. In his letters and speeches, Zinder combined a deep respect for the country that had welcomed his immigrant parents with a firm belief in the need for a free exchange of scientific information.

This archive is not just about one geneticist. It’s a mirror of an era in which science stopped being merely a matter of laboratories and moved into big politics, society, and international relations.