Sometimes, islands naturally become peninsulas over the course of centuries, but this is not one of those stories. Why wait centuries when you can make it happen in a single year? That’s exactly what NYC Parks Commissioner Robert Moses decided to do when he connected Hunter Island to the mainland to create a spacious beach for residents and visitors. In this article, we’ll tell the story of how Hunter Island was transformed into a peninsula. All this and more on bronx.name.

The Island’s Earliest Inhabitants

Like the rest of what is now New York City, Hunter Island was once inhabited by Native American tribes. Historical records mention the Siwanoy tribe, who lived in the area of today’s Pelham Bay Park. The Siwanoy held this particular island in high regard, and it was home to several sacred stones.

One of these, the “Gray Mare” stone, located on the island’s northwestern shore, served as a site for various tribal ceremonies. Another, the “Mishow” stone, was also an important ceremonial site where the burial of two Siwanoy sachems was discovered. It is known that Wampage II, a Siwanoy sachem, had a fortified residence on Hunter Island in the 17th century.

The island also played a crucial role in providing food for the tribe, as fishing was a key activity here. On some days, fishermen on the eastern shore of the island would catch over a thousand pounds of fish.

After the Englishman Thomas Pell purchased the land from the Native Americans in 1654, Hunter Island became part of his estate. The island later came into the possession of Alexander Henderson and was for a time named Henderson’s Island in his honor. Following his death in 1804, the island was offered for lease.

John Hunter and His Hunting Lodge

John Hunter, a successful businessman and politician, fell in love with the area, but he didn’t want to be a simple lessee. He dreamed of owning the entire island and spending the rest of his life there. After selling all his property, Hunter was able to raise enough funds to purchase the island. In 1813, he moved there with his wife Elizabeth and son Elias and built his own mansion. It was described as one of the finest houses of its time, with three stories, a large veranda, and terraces that sloped down to the shore. The building was rectangular, and its main entrance, with large doors framed by columns, faced west toward the mainland. The mansion housed a significant art collection of over 400 works by artists such as Rembrandt and Leonardo da Vinci. The house was situated on the highest point of the island, 27 meters above sea level, offering views of Long Island Sound and the Pelham Hills.

John Hunter lived in the estate until his death in 1852, after which ownership passed to his son, Elias. Following Elias’s death in 1865, his son John III was surprised to learn he could not become the sole owner of the island. His grandfather, who had dreamed of the island remaining a stronghold for his family, had stipulated in his will that his descendants could only inherit the land on one condition: they had to live there permanently, never leaving the family estate. However, John III had other plans and saw no future in living on a secluded, remote island. He wanted to be in the midst of the bustling city. So, in 1866, John Hunter’s grandson sold the land to Mayor Ambrose Kingsland. Over the next 23 years, the island changed hands several more times, with ownership passing to Alvin Higgins, Gardiner Journeay, and Oliver Iselin.

In the 1880s, New York City was undergoing major changes, particularly in recreational zoning. The NYC Parks Department seriously committed to a series of urban park projects. In 1888, Pelham Bay Park was opened, followed by Bronx Park in 1889. You can read about the creation of these parks by following the links here: Pelham Bay, Bronx Park.

Given that Hunter Island was located not far from the shore of the newly created Pelham Bay Park, it’s no surprise that a year later, the Parks Department expressed interest in adding it to the park area. In 1889, the city purchased the land for $324,000 (the equivalent of $11 million in 2023). There were many people eager to move into the former Hunter mansion. Living on an island surrounded by beautiful nature and a new park was a true dream.

In 1892, Stephen Peabody was granted a lease on the Hunter mansion for $1,200 a year and became the island’s caretaker. Soon after, the mansion was converted into a children’s shelter.

From Island to Peninsula

In the early 1900s, Hunter Island became a popular summer retreat, and a campground was opened there. The former mansion was converted into a hotel. In 1903, due to an increase in visitors, NYC Parks opened another campground at Rodman’s Neck, south of the island. By 1917, about half a million tourists were visiting Hunter Island annually.

However, by the 1920s, the condition of Pelham Bay Park began to deteriorate. The island also lost its appeal as European immigrants started squatting there, building shelters and tent cities.

In 1934, NYC Parks Commissioner Robert Moses took action. He decided to create one large beach that could serve everyone. To do this, he needed to connect Hunter Island to the shoreline. First, Moses dealt with the squatters, winning a court case against the unofficial tent encampments in the park. After that, he implemented his plan by filling in part of LeRoy’s Bay. In this way, the former island became part of one large beach, Orchard Beach. You can read more about the history of this public beach in this article.

The eastern part of Hunter Island is adjacent to the smaller islands of Hog Island and Cat Briar, which are located in Pelham Bay. Hunter Island is also connected to Twin Island on its southeastern edge. Twin Island was once two separate parts—East and West Twin Islands—and the western part was connected to Hunter Island by a man-made stone bridge that is now in ruins. Twin Island is also attached to another former island known as Two Trees Island. Today, these islands are connected to Hunter Island and the mainland. Orchard Beach, in a crescent shape, surrounds the bay from the east. The bay once adjoined the southern part of Hunter Island, but about a third of it was filled in to create Orchard Beach. The Hunter mansion was demolished during the construction in 1937.

In the 1960s, there were plans to expand the landfill in Pelham Bay Park. Officials pushed to create another landfill on the Hunter Island peninsula, away from the beach area. But a group of environmentalists led by Dr. Theodore Kazimiroff advocated for the creation of a wildlife sanctuary on the site where the landfill expansion was planned.

In 1967, Mayor John Lindsay signed a bill to create two preserves in Pelham Bay Park: the Thomas Pell Wildlife Sanctuary and the Marine Zoological and Geological Preserve on Hunter Island. In 1986, the Kazimiroff Nature Trail and the Pelham Bay Park Environmental Center were opened.

Unique Nature

The peninsula’s flora consists primarily of sections of old-growth forests that predate the settlement of New York, as well as plants brought by John Hunter in the 19th century. A 2005 study by the NYC Parks Department identified 49 native plant species and 4 invasive ones. Some of them are very rare, such as lousewort, alumroot, and broad beach fern.

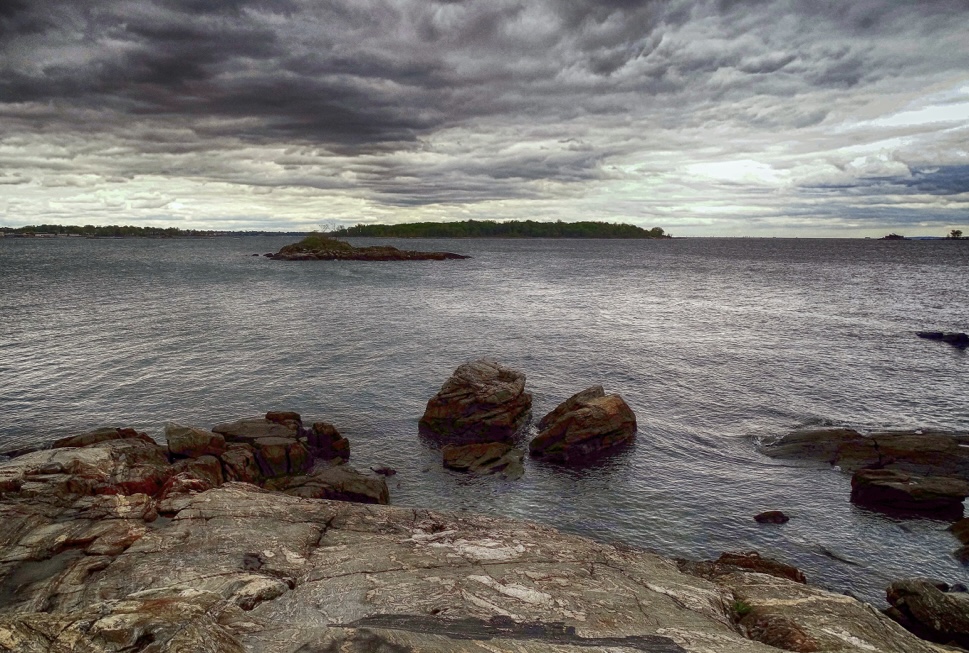

The Hunter Island Marine Zoological and Geological Preserve encompasses Twin Island, Cat Briar Island, Two Trees Island, and the northeastern part of Hunter Island. It contains many glacial erratics—large boulders left behind after the last ice age. The rocky coastline of the Twin Islands contains the southernmost outcrop of Hartland schist, a primary component of New England’s coastal bedrock, as well as granite with migmatite dikes and quartz veins. The preserve supports a unique marine tidal ecosystem that is rare in New York State.

Here you’ll find the largest continuous oak forest in Pelham Bay Park, which includes white, red, and black oaks, black cherry, white poplar, white pines, spruces, and locust trees. You can also find grape hyacinth, periwinkle, daylilies, and Tatarian honeysuckle, which were once part of the Hunter estate’s garden. The islands’ salt marsh ecosystem includes herons, cormorants, fiddler crabs, horseshoe crabs, sea worms, barnacles, and oysters.