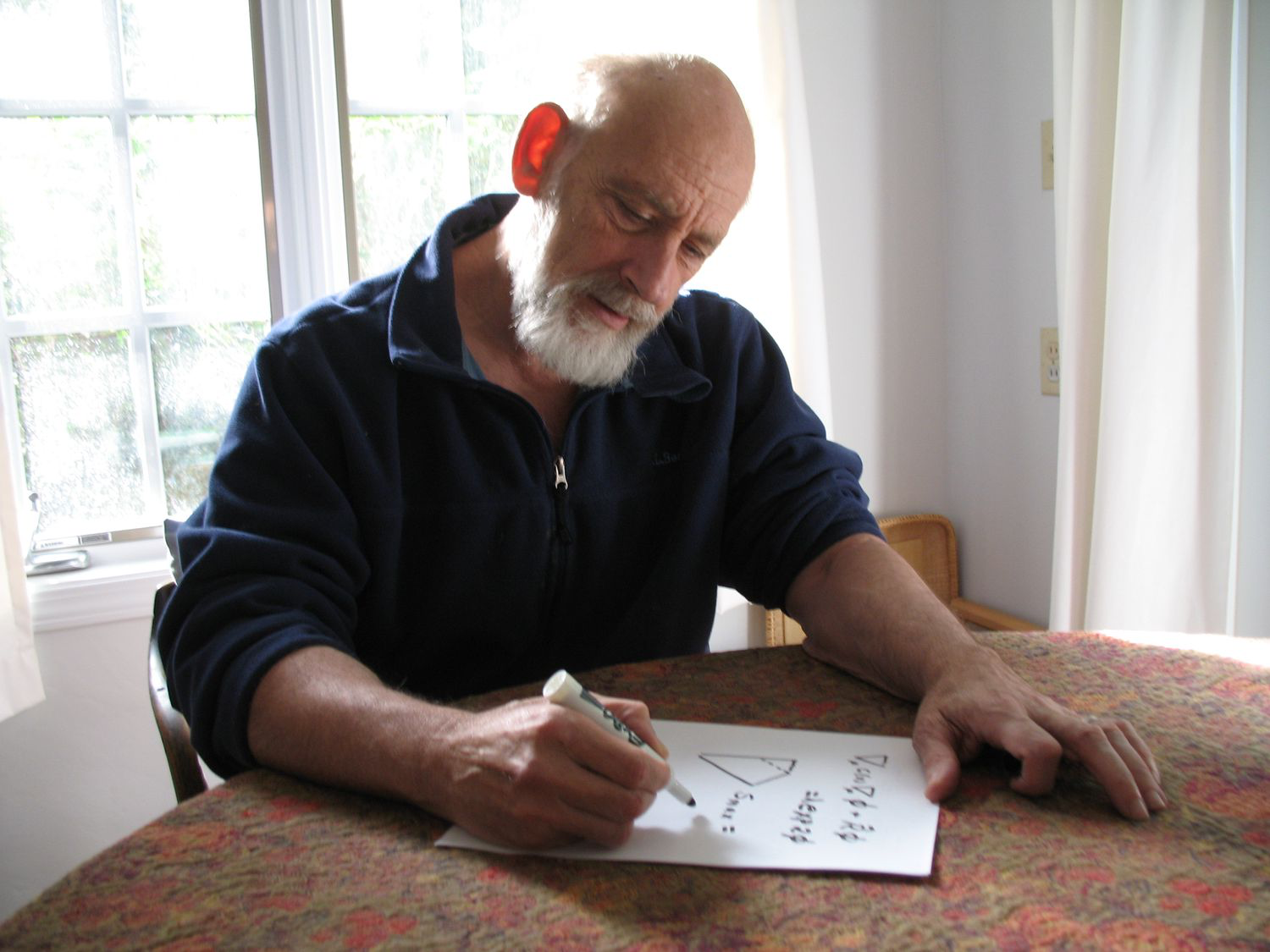

An American theoretical physicist and one of the leading scientists in modern fundamental physics. His research focuses on string theory, quantum field theory, quantum statistical mechanics, and quantum cosmology. In the world of science, Susskind is most often mentioned in discussions of black holes—one of the greatest mysteries of the universe. Read on bronx.name to learn more about the life and research of this distinguished scientist.

The Plumber’s Son

Leonard Susskind was born in 1940 into a Jewish family in the South Bronx. His childhood was spent in working-class neighborhoods, surrounded by his parents’ daily struggles to provide for the family. At the age of 16, Leonard started helping his father and even filled in for him at his plumbing job when he was sick. This first encounter with hard physical labor didn’t diminish his curiosity about the world.

Despite his difficult circumstances, Susskind was always drawn to science. He initially enrolled at the City College of New York in the engineering program, planning to study mechanical engineering. However, a serious conversation with his father forever changed his path. When Leonard said he wanted to become a physicist, his father, poking him with a plumbing pipe, said:

“You’re not going to be an engineer. You’re going to be Einstein.”

These words were prophetic. In 1962, Leonard earned a bachelor’s degree in physics, abandoning his engineering plans for good. His further studies led him to Cornell University, where he earned his Ph.D. in 1965 under the supervision of Peter Carruthers. It was there that Susskind discovered the concept of quarks (the fundamental building blocks of matter) and became fascinated with elementary particle physics, laying the groundwork for his future revolutionary work in string theory.

A Scientific Career

Leonard Susskind has made significant contributions to numerous fields of theoretical physics, including:

- The independent discovery of a string theory model for elementary particle physics.

- The theory of quark confinement.

- The development of Hamiltonian lattice gauge theory (Kogut-Susskind fermions).

- The theory of scaling violations in deep inelastic electroproduction.

- A theory of symmetry breaking known as “technicolor.”

- The second, independent theory of cosmological baryogenesis.

- The idea of the holographic principle and M-theory.

- The introduction of holographic entropy bounds into physical cosmology.

- The idea of the string theory anthropic landscape.

His scientific journey took him to Yeshiva University (1966–1979), Tel Aviv University (1971–1972), and Stanford University, where he has worked since 1979. Since 2007, Susskind has also been an associate member of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Canada.

In 1970, while still a young physicist, Leonard Susskind happened to be in an elevator with Murray Gell-Mann, a renowned theoretical physicist. Gell-Mann asked what Susskind was working on. He replied that he was exploring the idea that particles could be imagined as elastic, vibrating “strings,” like a rubber band. Hearing this, Gell-Mann burst out laughing—loudly and sarcastically. But this didn’t discourage Leonard; he began to work on his theory with even greater inspiration and determination. And he worked until he proved that he deserved applause, not mockery.

Leonard Susskind is a prime example of how curiosity and perseverance can take a person from a working-class Bronx neighborhood to global scientific fame.

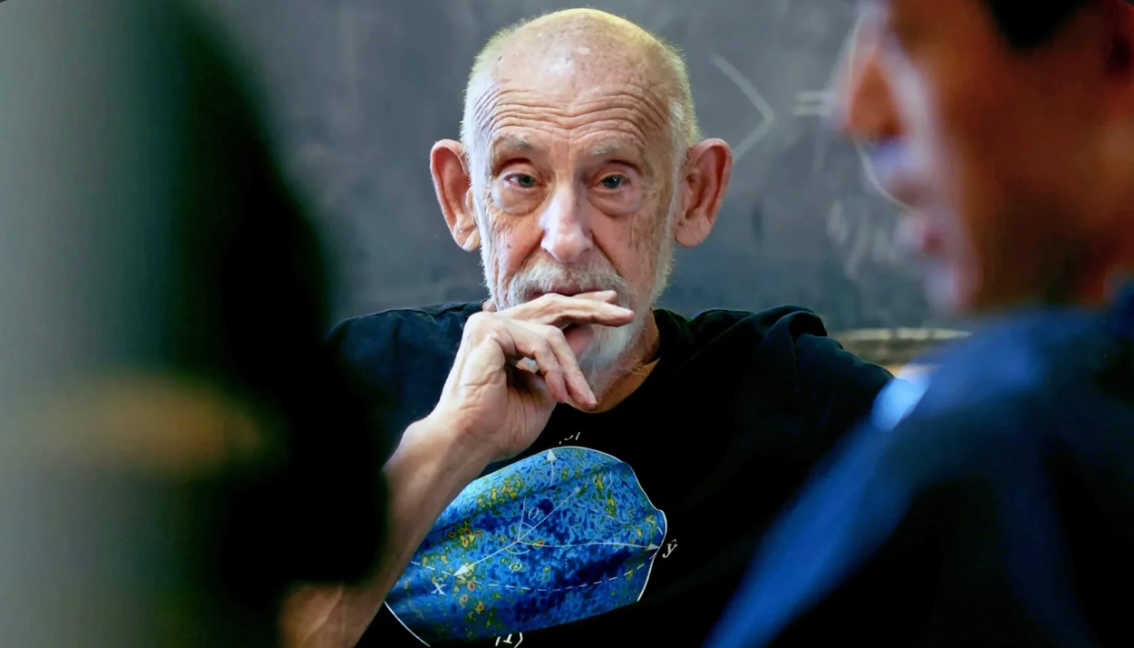

Black Hole Research

Leonard Susskind is known first and foremost for his work on string theory and the quantum physics of black holes. String theory replaces the notion of point particles with one-dimensional “strings” that vibrate. These strings can be used to describe particles in an atomic nucleus as well as gravitational effects, including the graviton—a hypothetical particle that mediates gravity.

Susskind particularly distinguished himself in black hole research. He showed that black holes don’t just absorb everything forever; they have their own thermodynamics and entropy—a measure of the amount of information that can be stored within them. The surface area of a black hole’s event horizon determines how much information it can “remember.”

Even more revolutionary was his work on the holographic principle. Imagine a black hole as a computer hard drive, where all the information that falls inside is encoded on its surface (the event horizon), rather than being lost in its volume. This ensures the conservation of quantum information and allows black holes to be reconciled with the fundamental laws of quantum mechanics.

This idea became the basis for the so-called “Black Hole War”—a debate between Susskind and Stephen Hawking. Hawking initially claimed that black holes lose all information irrevocably, which contradicts the laws of quantum mechanics. Susskind argued that information is not destroyed but is stored on the event horizon, and only over time can it leak out in the form of highly scrambled radiation. In 2004, even Hawking conceded that information is not completely lost, agreeing with his opponent’s key ideas.

Susskind also developed the theory of black hole entropy and the principle of black hole complementarity, which explain how physical laws work within the event horizon and that observers from different perspectives see different versions of reality.

His research has spurred modern quantum gravity and the theory of the multiverse. Using string theory and holography, Susskind explained why the cosmological constant (the parameter that defines the energy of a vacuum) is so small and how this is consistent with the possibility of life existing in our universe.

In simple terms, here’s Susskind’s view on black holes:

- Black holes store information.

Everything that falls inside is not destroyed but is encoded on the event horizon.

- The Holographic Principle.

All the information in a volume of space can be stored on its boundary—like a hologram.

- Hawking Radiation.

Black holes are not eternal. They very slowly radiate energy and, possibly, some of the encoded information.

- Entropy.

The area of the event horizon determines how much information a black hole can contain.

- Conservation of Quantum Laws.

Information is not lost, and this allows black holes to be reconciled with quantum mechanics.

Thanks to these ideas, Susskind changed the understanding of black holes. They are no longer just “all-devouring” objects but complex quantum systems with their own information structure that affect the fundamental laws of the universe.

Legacy and Recognition

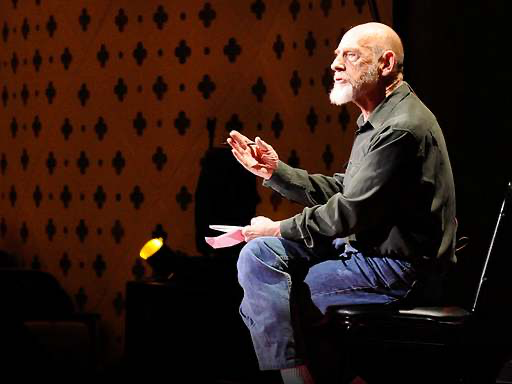

Leonard Susskind has left an undeniable mark on modern physics, combining a brilliant mind with an incredible imagination. His colleagues have always noted Susskind’s ability to think outside the box and to open up new horizons in the understanding of elementary particles and fundamental forces.

His achievements have been recognized with numerous awards: the Sakurai Prize for pioneering contributions to string theory, quantum chromodynamics, and dynamical symmetry breaking; the Pomeranchuk Prize; and the Oscar Klein Medal. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciencesand the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as a distinguished professor at the Korea Institute for Advanced Study.

However, Susskind’s true legacy is more than just awards. His books and lectures have made complex physics concepts accessible to a wide audience. From “The Cosmic Landscape,” where he explains the string theory anthropic landscape, to “The Black Hole War,” where he recounts his dispute with Stephen Hawking over the black hole information paradox, Susskind transforms abstract ideas into captivating stories.

His lecture and book series, “The Theoretical Minimum,” has become another important part of his legacy. He has educated generations of physicists, combining rigorous scientific accuracy with accessible teaching, and has shown that even the most complex concepts can be made understandable if approached with clarity and passion. His research continues to influence physics and inspire new generations of researchers. Leonard Susskind has left a legacy that combines scientific discoveries, educational initiatives, and the ability to inspire—and this legacy will be felt for years to come.